Shawneetown Fault Zone

Part of the Rough Creek-Shawneetown Fault System

Location

Northeastern Pope, southeastern Saline and

southern Gallatin Counties (J-7 and pl. 2)

References

Owen 1856, Butts 1925, J. Weller 1940, Baxter et al. 1967, Nelson and Lumm 1986 a, b, c, 1987

Description

The name Shawneetown Fault Zone is applied to the portion of the Rough Creek-Shawneetown Fault System that is in Illinois.

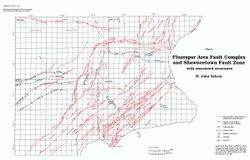

The Shawneetown Fault Zone enters Illinois just south of Old Shawneetown in Gallatin County and trends westward for about 15 miles (24 km). In southeastern Saline County the fault zone curves sharply to the south-southwest and continues about 12 miles (19 km) to Section 25, T11S, R6E, Pope County, where it intersects the Lusk Creek Fault Zone. Along most of its length the Shawneetown Fault Zone is well expressed topographically by a range of hills of resistant lower Pennsylvanian Caseyville Formation south and southeast of the fault zone. These include several of the highest points in southern Illinois: Williams Hill (elevation 1,064 feet, 324.3 m), Wamble Mountain, and Cave Hill. The fault zone itself tends to form a strike valley and is concealed by alluvium or glaciolacustrine deposits in many places.

The fault zone ranges in width from a few yards (meters) to as much as 8,000 feet (2,400 m). The largest fault in the zone is near the north edge of the east-west-trending part of the zone and it exhibits as much as 3,500 feet (1050 m) of vertical separation. Well penetrations show this to be a high-angle reverse fault dipping about 70°S. Nelson and Lumm (1986 a, b, c, 1987) have referred to this as the front fault. It apparently continues the full length of the [[Rough Creek-Shawneetown Fault System]] in Kentucky, as indicated by seismic reflection data and repeated section in boreholes. The front fault probably continues to the western terminus of the Shawneetown Fault Zone, but definite proof of reverse faulting is not available along the south-southwest-trending portion of the zone.

Other faults in the Shawneetown Fault Zone strike subparallel to the front fault and have throws measured in hundreds of feet. Some of these join the front fault at one or both ends and probably connect with it at depth, but other faults appear to be isolated. In places the fault zone assumes a braided pattern with interconnected faults outlining a series of polygonal or lens-shaped slices. This is shown best in the area where the fault zone bends in Saline County (Nelson and Lumm 1986c) and in the Herod Quadrangle between Wamble Mountain and the intersection with the Lusk Creek Fault Zone (Baxter et al. 1967). Most of the smaller faults in the Shawneetown Fault Zone probably are normal faults.

Although displacements on individual faults are large, the net offset across the fault zone is small. Pennsylvanian coal beds in the Eagle Valley Syncline south of the fault zone lie at the same or slightly lower elevation as the same beds north of the fault zone. Southwest of the syncline a block composed mainly of Caseyville Formation and upper Chesterian strata is uplifted between the Shawneetown and Herod Fault Zones. Net uplift in this area is on the order of 300 to 500 feet (90-150 m). Large displacements in the Shawneetown Fault Zone are the result of sharp tilting and upthrow of slices adjacent to the front fault. The most extreme case is at a place called the "Horseshoe Upheaval" in Section 36, T9S, R7E, just west of the Saline-Gallatin county line (Nelson 1987c). At this point a slice of nearly vertical Mississippian Fort Payne Formation and Upper Devonian New Albany Group south of the front fault is juxtaposed with middle Pennsylvanian strata north of the fault (fig. 66). An oil test hole 0.75 mile (1.2 km) west of the Horseshoe Upheaval penetrated the front fault and passed from Lower Devonian chert above into Pennsylvanian strata below. The vertical separation at both places is approximately 3,500 feet (1,050 m), which is the largest known offset on any near-surface fault in Illinois. At numerous other places tilted blocks of Mississippian strata are upthrown between Pennsylvanian rocks along the fault zone.

Rocks north and northwest of the Shawneetown Fault Zone are mostly horizontal or gently dipping. In the fault slices and immediately south or southeast of the fault zone, the rocks generally dip steeply south or southeast and strike parallel with the faults. These dips rapidly diminish away from the fault zone.

The presence of the upthrown slices and the steep tilting of strata along the fault zone imply that two periods of movement took place after Pennsylvanian sedimentation. The first movement was reverse with the south or southeast side upthrown; the second movement involved normal faulting with the south or southeast side downdropped (Nelson and Lumm 1987).

No oil production has been achieved in or south of the Shawneetown Fault Zone, although numerous fields have been developed in and south of the Rough Creek-Shawneetown Fault System in adjacent parts of Kentucky. Small-scale mining and prospecting for fluorite and associated minerals have taken place along the southwest-trending portion of the Shawneetown Fault Zone.