Du Quoin Monocline

Location

Closely follows Third Principal Meridian from northeastern Jackson to northwestern Marion County (H-5 to J-5)

References

Kay 1915, Fisher 1925, Cady et al. 1938, Clark and Royds 1948, Siever 1951, Brownfield 1954, Bristol and Buschbach 1973, Keys and Nelson 1980, Nelson 1981, Stevenson et al. 1981, Treworgy 1988, Whitaker and Treworgy 1990

Description

The Du Quoin Monocline separates the Sparta Shelf on the west from the Fairfield Basin on the east. Probably more than 100 published reports mention the Du Quoin Monocline in passing; only a few have devoted detailed attention to its nature, age, or origin.

Although called an anticline in many early reports, the Du Quoin is a monocline with the east side downwarped. From the north side of the Cottage Grove Fault System, it trends northeastward for several miles and gradually curves due northward (fig. 31). Near the northeast corner of Perry County, the flexure splits: the west branch continues northward and the east branch veers to the northeast. The west branch flattens out and loses its identity in northwestern Marion County, whereas the east branch curves toward and merges with the east flank of the Salem Anticline.

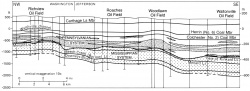

The Du Quoin Monocline has a long geologic history. It may have affected St. Croixan sedimentation; scattered boreholes indicate the Mt. Simon Sandstone to be thin or absent on the Sparta Shelf but well developed in the Fairfield Basin. A seismic profile (fig. 32) showing slight eastward thickening of the Knox Group across the monocline, suggests continued folding into the Canadian Epoch. Silurian and Devonian strata thin westward across the Sparta Shelf, but thickness patterns point to gentle tilting rather than development of a sharp flexure. Effects of the monocline on Mississippian sedimentation were, at most, modest. Treworgy (1988) attributed fades changes in the Golconda Group (Chesterian) to slight movement along the flexure. The monocline definitely was developing by the end of the Mississippian Period; the sub-Pennsylvanian erosional pattern suggests southward deflection of pre-Pennsylvanian streams that approached it (Bristol and Howard 1971). The greatest uplift took place, however, during the early part of the Pennsylvanian Period. Strata of this age abruptly thicken eastward by several hundred feet across the flexure (fig. 33). Intermittent movement continued during later Pennsylvanian time and is reflected by thickness and fades changes of individual beds or members. For example, the Springfield Coal Member is 4 to 5 feet (1.2-1.5 m) thick on the east side of the monocline, but it is thin or absent to the west. The younger Herrin Coal Member, in contrast, crosses the fold without change of thickness. Post-Pennsylvanian movement is documented by development of several hundred feet of structural relief on Desmoinesian and younger Pennsylvanian horizons.

Because of this progressive deformation, the structural relief of the monocline is greater on pre-Pennsylvanian than on Pennsylvanian horizons. Maximum elevation change of the Herrin Coal is about 550 feet (165 m) (Cady et al. 1938), but the Beech Creek ("Barlow") Limestone (Chesterian) rises more than 1,000 feet (300 m) in the same place (Bristol 1968). The New Albany Group (Stevenson et al. 1981) and Galena Group (Bristol and Buschbach 1973) also show approximately 1,000 feet (300 m) of maximum relief across the monocline. These maps are based on far fewer control points than the maps of the Beech Creek Limestone and Herrin Coal.

A proprietary seismic reflection profile across the Du Quoin Monocline in Perry County (fig. 32) shows the monocline affecting all Paleozoic reflectors. The deepest continuous reflector on this profile was believed to represent the base of the Knox Group above the Mt. Simon Sandstone. No faulting could be discerned on the seismic section. Yet the rather sharp hinge on the lower step of the fold suggests the possibility of a basement fault that does not offset the Knox. The Du Quoin Monocline shares many characteristics, including a branching pattern, with the classic Laramide monoclines of the Colorado Plateau and Rocky Mountains. Laramide monoclines overlie faults in Precambrian crystalline basement (Davis 1978, Lisenbee 1978, Reches 1978).

The Dowell and Centralia Fault Zones, zones of normal faulting, follow the dipping flank of the Du Quoin Monocline. These faults displace strata down to the west, whereas the monocline warps beds down to the east. The faults are known from coal mine exposures in Pennsylvanian rocks and from missing sections of Mississippian strata in well records. Seismic profiles indicate that the Centralia Fault Zone extends downward at least to Ordovician rocks with no loss of displacement. These faults, therefore, are not merely superficial features or adjustments to folding. Brownfield (1954) hypothesized that the Du Quoin Monocline was produced by compression and that the faults developed during a later (post-Pennsylvanian) episode of extension.

Brownfield's hypothesis seems to be the most likely explanation for the structure.

References

Figure(s)

|